Rediscovering the Future

Who am I

- Conrad Ludgate (he/him) - https://conradludgate.com/

- I do Rust systems programming at Neon - https://neon.tech/

- I like Rust

What will this workshop cover

Many people use async Rust, but my feeling is that a lot of people don't understand it. I think that's a shame. I hope to give you the seed of an idea that will kick start some of you to investigate these systems further.

My the end of the session today, we should have some key components of an async Rust system built. They won't be efficient or suitable for production use, but I reckon it's a good basis to start with.

Chapter 0 - Getting started with Tokio

Tokio is an "asynchronous runtime" for Rust.

Asynchronous execution

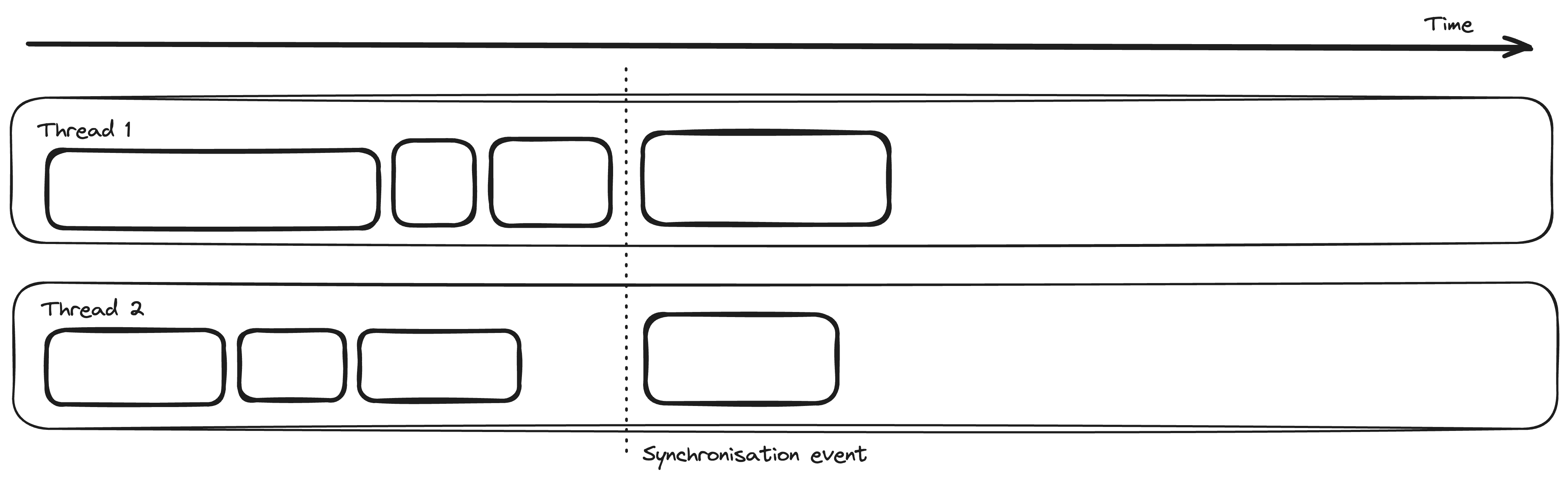

Asynchronous execution means the lack of synchronous execution. Synchronous execution means that tasks are executed in a synchronised fashion. This could mean that a synchronous task will wait for the previous task to complete before it continues.

Some tasks are necessarily synchronous, but not all tasks need to be synchronised together. For example, one thread can execute a synchronous set of tasks, but it is asynchronous with all the other threads by default. We can then resynchonrise threads at specific points using features like Mutexes and Channels

In Rust, asynchronous execution often holds a stronger cultural meaning, which means it uses

the async/.await features of Rust. This is what we mean when we say that Tokio is an "asynchronous runtime".

Tokio depends directly on the async features built into the Rust language.

Runtime

A runtime is a very abstract term. People often say that Rust has no runtime, which is or isn't true depending on who you ask.

A runtime is just a piece of software that manages some components for you. For example:

- An Operating System is a runtime over the hardware

- A memory allocator is a runtime over the system memory pages

- libc is a runtime over unix-style operating systems

Rust has a very minimal runtime on top of the runtimes listed above. The Rust runtime manages setting up the main entrypoint in an application, thread execution, as well as setting up panic routines.

So why do people say that Rust has no runtime? Compared to some other languages, Rust's runtime is a lot less involved. After process or thread startup, Rust does not run any code that you didn't yourself write.

- Compared to an interpreted language, which has a runtime that parses each statement and executes it.

- Compared to a JIT compiled or Bytecode VM language, which dynamically compiles and recompiles instructions to a native optimised representation at runtime.

- Compared to a garbage-collected language, which regularly sweeps working memory to detect unused allocations and reclaim them.

- Compared to a language with green threads, which has its own thread scheduling system built in and regularly forces tasks to yield.

So, is this good or bad? For many uses of Rust, not having an intrusive runtime like a garbage collector or green-threads forced on your projects can be a very important thing. Perhaps you are developing some soft-realtime system where latency is incredibly important, you do not want the runtime slowing things down with a memory sweep or forced yield in the meantime.

However, not all applications have such strong requirements, thus you might opt for some convenience for getting good performance. In the case of Tokio, it is a runtime with a cooperative green-thread scheduler with support for async-io. Cooperative scheduling means that tasks are not forced to yield, but instead choose to yield at explicit points, but ultimately when the task does yield, it is up to Tokio to choose what task to run next and when the previous task will get to run again.

Task 0 - Creating our workspace

To set ourselves up for the remainder of the workshop, the project template can be found at https://github.com/conradludgate/eurorust-template. It contains all the dependencies you will need for the workshop. The project is structured to be ready to use straight away.

Task 1 - Using Tokio

In the project/00_tokio folder, we can see a simple async program. Let's go through step by step what we have here.

We shall start with the entrypoint. We must use the #[tokio::main] attribute if we want an async main function.

#[tokio::main] async fn main() { }

Let's next spawn some asynchronous tasks. Remember, these tasks execute synchronously relative to themselves, but are unsynchronise relative to all other tasks. Inside the main function we can write

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { tokio::spawn(async move { tokio::time::sleep(std::time::Duration::from_secs(2)).await; println!("hello after 2 seconds"); }) }

If you run this program, you will notice that likely nothing gets printed. This is of course because the task runs concurrently and is not being synchronised with the main function before our process terminates.

We can resynchronise by introducing a channel.

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

+ let (tx, mut rx) = tokio::sync::mpsc::unbounded_channel();

tokio::spawn(async move {

tokio::time::sleep(std::time::Duration::from_secs(2)).await;

println!("hello after 2 seconds");

+ tx.send(()).expect("channel should not be closed");

})

+ rx.next().await.unwrap();

}

For good measure, let's add another task and make our channels send some actual data.

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

+ let (tx, mut rx) = tokio::sync::mpsc::unbounded_channel();

let tx1 = tx.clone();

tokio::spawn(async move {

tokio::time::sleep(std::time::Duration::from_secs(2)).await;

println!("hello after 2 seconds");

tx1.send(1).expect("channel should not be closed");

})

+ let tx2 = tx.clone();

+ tokio::spawn(async move {

+ tokio::time::sleep(std::time::Duration::from_secs(1)).await;

+ println!("hello after 1 second");

+ tx2.send(2).expect("channel should not be closed");

+ })

- rx.next().await.unwrap();

+ let first = rx.next().await.unwrap();

+ let second = rx.next().await.unwrap();

+ println!("received {first} {second}");

}

Our program should look like

```diff #[tokio::main] async fn main() { let (tx, mut rx) = tokio::sync::mpsc::unbounded_channel(); let tx1 = tx.clone(); tokio::spawn(async move { tokio::time::sleep(std::time::Duration::from_secs(2)).await; println!("hello after 2 seconds"); tx1.send(1).expect("channel should not be closed"); }) let tx2 = tx.clone(); tokio::spawn(async move { tokio::time::sleep(std::time::Duration::from_secs(1)).await; println!("hello after 1 second"); tx2.send(2).expect("channel should not be closed"); }) let first = rx.next().await.unwrap(); let second = rx.next().await.unwrap(); println!("received {first} {second}"); }

and when run it should eventually output

received 2 1

Chapter 1 - Introducing the Future trait

If our asynchronous tasks are cooperative as we discussed before, how could we model that as a Rust trait?

Let's use the following async function as a reference point:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { async fn greet(name: String) { println!("hello {name}"); tokio::time::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1)).await; println!("goodbye {name}"); } }

We know that our task will run until some point, at which it will choose to pause and return. The current task state should be saved so that it can be resumed later. We can then resume the task until it either pauses again, or completes and returns a value. In the example above, we will be pausing at the sleep stage.

Since it has to update state, we know we will likely need a function that takes &mut self. Since the task will sometimes

return nothing as it pauses, and sometimes returns a value when it completes, we need an enum to track which state it is in

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { enum TaskProgress<T> { Waiting, Completed(T), } }

Maybe we can model our tasks with the following trait.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { trait Task { type Output fn resume(&mut self) -> TaskProgress<Self::Output>; } }

One problem. We have no way to distinguish between pausing because we are being polite, and pausing because we're blocked on some other task completing. We ultimately want some system that allows a task to inform the runtime of its ability to resume.

Maybe we can introduce some notification system which allows tasks to supply such notifications.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct ReadySignal(/* todo */); impl ReadySignal { fn announce_readiness(&self); } trait Task { type Output fn resume(&mut self, ready: ReadySignal) -> TaskProgress<Self::Output>; } }

If a task is pausing for politeness, then it can announce its own readiness before returning Waiting.

If a task is blocked on some other task, then it can synchronise with the task, providing the dependency task

with its ReadySignal. When the task completes, it can check if any signals were registered against it, then

announce the readiness.

Unveiling our Future, we see that this construction is not too different from what we have in std.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { enum Poll<T> { Pending, Ready(T), } struct Context<'a> { /* todo */ } struct Waker { /* todo */ } impl<'a> Context<'a> { fn waker(&self) -> &'a Waker; } trait Future { type Output; fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<Self::Output>; } }

Tutorial - State Machines

Let's again use the following async function as a reference point:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { async fn greet(name: String) { println!("hello {name}"); tokio::time::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1)).await; println!("goodbye {name}"); } }

and let's just remind ourselves of what a state machine looks like (we shall ignore Pin for now)

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { trait Future { type Output; fn poll(&mut self, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<Self::Output>; } }

Before we try to figure out what states we need to keep, let's consider the transitions instead.

The first transition is

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { println!("hello {name}"); tokio::time::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1)) }

The second transition is

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { println!("goodbye {name}"); }

Since we can pause at .await points, these have to be the places we save the states.

Then between the .awaits, including before the first and after the last, are our transition steps.

Since our async fn has only 1 await point, that will be our one intermediate state.

We will also have 2 more states to complement our transitions. One state for before the function runs, and one state for after the function is complete.

So let's see some code showing this off the states

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { enum GreetFut { Init { // Our initial state stores the argument of the function name: String, } Intermediate { // We must carry all values that are still in scope. name: String, // We must carry any intermediate futures that are still in progress sleep_fut: Sleep, } // When the future is done, there's no more values to store // as they have been dropped already. Done, } }

And now the transitions:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { impl Future for GreetFut { // our function returns nothing type Output = (); fn poll(&mut self, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<Self::Output> { loop { match *self { GreetFut::Init { name } => { // perform our first transition println!("hello {name}"); let sleep_fut = tokio::time::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1)); // update our state *self = GreetFut::Intermediate { name, sleep_fut }; // we need to try and continue the state machine continue; } GreetFut::Intermediate { name, mut sleep_fut } => { // check if we are ready to make the second transition ready!(sleep_fut.poll(cx)); // we are ready to perform our second transition println!("goodbye {name}"); // update our state again *self = GreetFut::Done; // since there are no more state, we should return ready return Poll::Ready(()); } // There is no state after done, so we cannot make any transition. GreetFut::Done => panic!("polled after completion"), } } } } }

Tangent - Pin

Pin is weird, but it's easy enough to understand. Let's explore a case study.

Case Study: Read

Let's take for granted that me might want to have an async read function. This is a reasonable assumption given that async Rust is often used in tandem with async-io. What might that look like?

Without async, that looks something like

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn file_read<'f, 'b>(file: &'f File, buf: &'b mut [u8]) -> io::Result<usize> { todo!() } fn demo<'f>(file: &'f File) { let mut buf = [0u8; 1024]; let n = file_read(file, &mut buf[..]).unwrap(); let s = String::from_utf8_lossy(&buf[..n]).unwrap(); println!("{s:?}"); } }

Maybe with async, we might theorize the API should look something like

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { async fn file_read<'f, 'b>(file: &'f File, buf: &'b mut [u8]) -> io::Result<usize> { todo!() } async fn demo<'f>(file: &'f File) { let mut buf = [0u8; 1024]; let n = file_read(file, &mut buf[..]).await.unwrap(); let s = String::from_utf8_lossy(&buf[..n]).unwrap(); println!("{s:?}"); } }

Let's see what the consequences of this API are.

As discussed previously, Async functions turn into state machines. We don't know the implementation of the file_read function, but

the type signature should look something like

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct FileReadFut<'f, 'b> { file: &'f File, buf: &'b mut [u8], _other_stuff: (), } }

We do however know the implemenation of demo, so let's try and put our skills to use and implement a state machine of the demo function.

We have 3 main states:

- Init

- Reading

- Done

between the states, we have some logic:

- Init -> Reading: we construct a buffer on the stack, and construct our file_read future.

- Reading -> Done: we parse the bytes as a string and print them

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { enum DemoFut<'f> { Init { file: &'f File, } Reading { buf: [u8; 1024]; file_read: FileReadFut<'f, 'b>, } Done } impl<'f> Future for DemoFut<'f> { type Output = (); // ignore pin for now :) fn poll(&mut self, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<()> { loop { match *self { Self::Init { file } => { let mut buf = [0u8; 1024]; let file_read = file_read(file, &mut buf[..]); *self = Self::Reading { buf, file_read }; // repeat the loop to process the next state continue; } Self::Reading { buf, file_read } => { // ready! returns early if the value is Poll::Pending let n = ready!(file_read.poll(cx)).unwrap(); let s = String::from_utf8_lossy(&buf[..n]).unwrap(); println!("{s:?}"); *self = Self::Done; // we are done, so break the loop and return ready break Poll::Ready(()); } Self::Done => panic!("resumed after completion"), } } } } }

Is there a problem with this?

There's a couple things wrong.

The first is the undefined lifetime in the definition of DemoFut. What we want it to borrow from buf, but how do we define that?

The second is the related borrow from buf after we move buf into the state machine.

I am not going to explain how to work around these problems. But we can agree that any such solution would necessitate so-called "self-referential" structs.

Let's make another assumption. Assume we can construct a self-referential type that the Rust memory model is happy with. Can we use such a value of that type the same as any other?

In rust, if you currently have ownership of a value, you can pass ownership somewhere else. This might cause the compiled code to move the value somewhere else in memory. Maybe we move it to the end of the stack to be passed into a function.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut demo_fut = DemoFut::Init(fut); let poll = demo_fut.poll(&mut some_context); assert!(poll.is_pending()); // move the value. send_somewhere_else(demo_fut); }

Pin is a system to ensure that these moves cannot happen. This is why we require the Future impl accept Pin<&mut Self>.

Tutorial - Pin

We will have to use Pin during this workshop, so let's explore the ways we can use pin.

Constructing pinned values.

Often, you don't need to construct any pinned values. When you use .await, Rust will automatically pin

the values accordingly. There are exceptions though.

There are 4 main ways to construct a pinned value:

Easy mode

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let pinned = Box::pin(value); }

Since the value on the heap has a stable address, we can use box to construct a self-referential safe value. This will always work and you can keep the owned value and pass around the owned value as usual.

Cheating mode

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let pinned = Pin::new(&mut value); }

Some values do not care about whether they are pinned or not. Such types are called Unpin. For example, a String is not self referential,

thus implements the Unpin trait. When a function requires such a pinned value but pinning is unnecessary,

usually in generics or traits, you can construct the Pin reference on demand with Pin::new.

Zero cost abstration

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let pinned = std::pin::pin!(value); }

If you never need ownership over the value, and just want to poll it, you can quite often pin inplace using this special macro. This avoids the cost of the allocation of Box. This works by internally moving and shadowing the value such that you cannot access it again. This is often known as stack-pinning, as opposed to the box-pinning we saw earlier.

I know what I am doing

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let pinned = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut value) }; }

If you know that the value is actually pinned, but cannot prove it to the compiler, you can use unsafe to construct a Pin manually.

We won't have to do this during today's workshop.

Pin Projections

Another common technique is pin projecting, where you take a pinned value, and can therefore assert that the contained values are also pinned.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Foo { bar: Bar, baz: Baz, } struct FooProjection<'a> { bar: Pin<&'a mut Bar>, baz: Pin<&'a mut Baz>, } fn project(foo: Pin<&mut Foo>) -> FooProjection<'_> { unsafe { let foo = Pin::into_inner_unchecked(foo); let bar = Pin::new_unchecked(&mut foo.bar); let baz = Pin::new_unchedked(&mut foo.baz); FooProjection { bar, baz } } } }

Because this is such a common pattern, there exist some tools that help you do it safely.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use pin_project_lite::pin_project; pin_project! { struct Foo { #[pin] bar: Bar, #[pin] baz: Baz, } } fn demo(foo: Pin<&mut Foo>) { // the project function is provided for us let _foo = foo.project(); } }

Reborrowing

An unfortunate downside of Pin being a library type and not a built in reference type is that there's no automatic reborrowing.

This means you will commonly see pinned_val.as_mut() littered around the codebase to re-borrow the value with a temporary shorter lifetime.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn demo(mut foo: Pin<&mut Foo>) { loop { // need to reborrow here so we don't move out of the loop. foo.as_mut().poll(some_context()); } } }

Task 1 - Writing a select future

Now that we have a basic understanding of some state machine ideas, and how to use Pin,

let's construct an async function that races two futures.

In your project template you will see the following code

use std::{future::Future, time::Duration}; #[derive(Debug)] enum Either<L, R> { Left(L), Right(R), } async fn select<A: Future, B: Future>(left: A, right: B) -> Either<A::Output, B::Output> { // REPLACE ME tokio::select! { left = left => Either::Left(left), right = right => Either::Right(right), } } #[tokio::main] async fn main() { let (tx, rx) = tokio::sync::oneshot::channel(); tokio::task::spawn(async { tokio::time::sleep(Duration::from_secs(2)).await; let _ = tx.send(()); }); let left = tokio::time::sleep(Duration::from_secs(3)); let right = rx; let res = select(left, right).await; println!("raced: {:?}", res); }

When run, we should expect to see the output

raced: Right(Ok(()))

If you adjust the sleep durations, we might see a different result.

I want you to write your own implementation of what select!() is doing here.

For some insight here, let's take a simple async function that just calls another async function F

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { async fn run_one<F: Future>(f: F) -> F::Output { f.await } }

We know how to write this with 3 states, but we can cheat here and try inlining.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn run_one<F: Future>(f: F) -> RunOneFut<F> { RunOneFut { f } } pin_project!{ struct RunOneFut<F> { #[pin] f: F, } } impl<F: Future> Future for RunOneFut<F> { type Output = F::Output; fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<Self::Output> { let this = self.project(); let output = ready!(this.f.poll(cx)); Poll::Ready(output) } } }

There's no need to add our own state machine on top when we know F will be managing the states for us.

Now, the key insight here is what ready! is doing. Let's expand it out.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { impl<F: Future> Future for RunOneFut<F> { type Output = F::Output; fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<Self::Output> { let this = self.project(); let output = match this.f.poll(cx) { Poll::Ready(output) => output, Poll::Pending => return Poll::Pending, } Poll::Ready(output) } } }

Let's flip the script, so to speak, and return the ready result early and only return pending afterwards.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { impl<F: Future> Future for RunOneFut<F> { type Output = F::Output; fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<Self::Output> { let this = self.project(); match this.f.poll(cx) { Poll::Ready(output) => return Poll::Ready(output), Poll::Pending => {}, } Poll::Pending } } }

In theory, there's nothing stopping you from doing something else before returning pending...

Chapter 2 - Writing an async mpsc channel

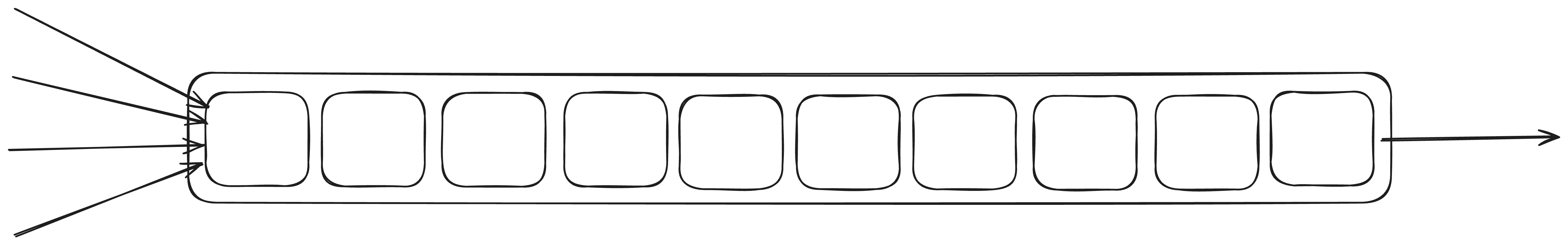

A "multi-producer, single-consumer" (mpsc) channel, is a synchronized queue of data. Many tasks can send data into the queue ("produce" values), and only a single value can receive data from the queue ("consume" values).

The mpsc channel is the bread and butter of synchronization primitives as it allows efficient sharing of data between tasks.

Because of the Rust ownership model, you can ergonomically encode the "single consumer" requirement into the type system. Let's take a peek at the mpsc in std.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub fn channel<T>() -> (Sender<T>, Receiver<T>); impl<T> Sender<T> { /// This method will never block the current thread. pub fn send(&self, t: T) -> Result<(), SendError<T>>; } impl<T> Clone for Sender<T> {} impl<T> Receiver<T> { /// Attempts to wait for a value on this receiver. pub fn recv(&mut self) -> Result<T, RecvError>; } }

What std doesn't clarify here is that recv() will block our runtime thread,

not allowing it to poll other tasks that are also on our thread. This is not great, so let's

figure out how we could possibly make one with support for async code.

Since there's only one function that will wait here, there's only one function that needs to be made async. That's what we will be looking at soon.

Tangent - Channel shutdown

Before we cover how to write an async channel, let's first cover the edge-cases we will need to consider.

Closing the receiver

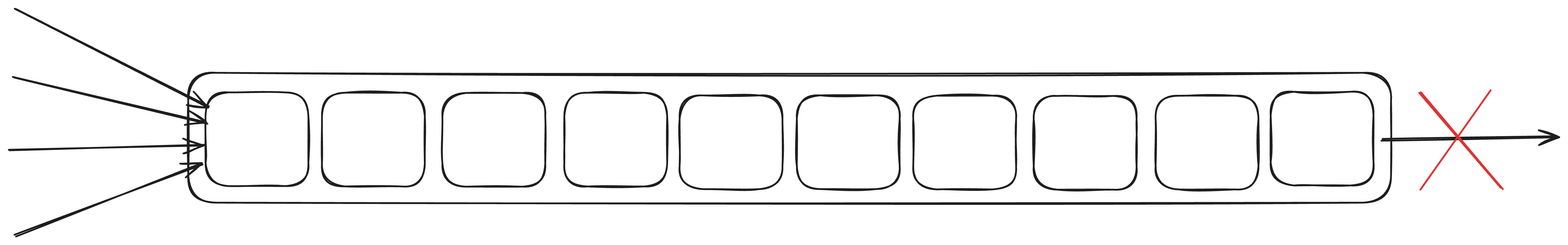

It's possible that we have dropped the receiver of a channel while still having some of the senders alive. Ideally they will gracefully handle when there are no tasks that will possibly listen to the message, and not bother wasting memory. Perhaps also returning a value to indicate that it was closed.

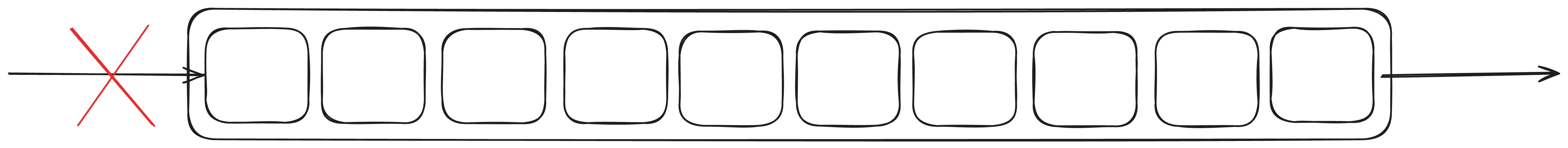

Closing the senders

It's also possible that we have dropped all the senders of a channel while the receiver is still alive.

We could get lucky and we might not currently be waiting on a value. When we finally try to receive a value, we could check if there are any senders.

However, another edge case that shows up is when we are currently waiting for a value from the channel, and the last sender is dropped. In this case we would somehow need to notify the channel receiver that it is time to give up the waiting.

Task 1 - Writing our own mpsc

Let's write a very in-efficient mpsc channel.

Since we want a queue of data, let's model it with a VecDeque. Since we want this queue to be shared across tasks and threads,

we will want to make use of Arc and Mutex.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Channel<T> { queue: VecDeque<T>, } struct Receiver<T> { channel: Arc<Mutex<Channel<T>> } struct Sender<T> { channel: Arc<Mutex<Channel<T>> } }

When sending data to the channel, it is as simple as locking the mutex, and pushing to the back of the queue.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { impl<T> Sender<T> { pub fn send(&self, value: T) { let mut channel = self.channel.lock().unwrap(); channel.queue.push_back(value); } } }

Now, let's recall the edge-cases we discussed earlier. One of them was that it's possible there's no receiver anymore.

Let's handle that by keeping track of whether the receiver is still active, and return an error when trying to send.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Channel<T> { queue: VecDeque<T>, /// true if there is still a receiver receiver: bool, } impl<T> Drop for Receiver<T> { fn drop(&mut self) { let mut channel = self.channel.lock().unwrap(); channel.receiver = false; } } impl<T> Sender<T> { pub fn send(&self, value: T) -> Result<(), T> { let mut channel = self.channel.lock().unwrap(); if !channel.receiver { return Err(value) } channel.queue.push_back(value); Ok(()) } } }

Now, that covers the sending side, but how do we receive data? In the happy case, there will always be data ready immediatly that we can read

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { impl<T> Receiver<T> { pub async fn recv(&mut self) -> Option<T> { let mut channel = self.channel.lock().unwrap(); channel.queue.pop_front() } } }

But we also want to make sure we can wait for a message if there are currently none. To do so,

we will need to utilise the Waker.

We will use std::future::poll_fn for convenience:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Channel<T> { queue: VecDeque<T>, /// true if there is still a receiver receiver: bool, /// which receiver task to notify recv_waker: Option<Waker>, } impl<T> Receiver<T> { pub async fn recv(&mut self) -> Option<T> { std::future::poll_fn(|cx| { let mut channel = self.channel.lock().unwrap(); // if we have any values available, immediately return ready if let Some(value) = channel.queue.pop_front() { return Poll::Ready(Some(value)); } // if there are no values, register our waker and return pending channel.recv_waker = Some(cx.waker().clone()); Poll::Pending }).await } } }

Now, we just need to make senders wake up the task, if there is one currently waiting.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { impl<T> Sender<T> { pub fn send(&self, value: T) -> Result<(), T> { let mut channel = self.channel.lock().unwrap(); if !channel.receiver { return Err(value) } // wake up the receiver if let Some(waker) = channel.recv_waker.take() { waker.wake(); } channel.queue.push_back(value); Ok(()) } } }

Now, there's just the last edge-case to cover. We need to keep track of how many Senders are still attached to the channel,

and action on it accordingly. Let's start by adding a count to the channel, and cancel the recv if the count is 0.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Channel<T> { queue: VecDeque<T>, /// true if there is still a receiver receiver: bool, /// number of senders we have senders: usize, /// which receiver task to notify recv_waker: Option<Waker>, } impl<T> Receiver<T> { pub async fn recv(&mut self) -> Option<T> { std::future::poll_fn(|cx| { let mut channel = self.channel.lock().unwrap(); // if we have any values available, immediately return ready if let Some(value) = channel.queue.pop_front() { return Poll::Ready(Some(value)); } // return early, do not wait, if there are no more senders if channel.senders == 0 { return Poll::Ready(None); } // if there are no values, register our waker and return pending channel.recv_waker = Some(cx.waker().clone()); Poll::Pending }).await } } }

We also need to implement the correct accounting for the sender count

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { impl<T> Clone for Sender<T> { fn clone(&self) -> Self { let mut channel = self.channel.lock().unwrap(); channel.senders += 1; Self { channel: Arc::clone(&self.channel) } } } impl<T> Drop for Sender<T> { fn drop(&mut self) { let mut channel = self.channel.lock().unwrap(); channel.senders -= 1; // wake up the receiver if there are no more senders if channel.senders == 0 { if let Some(waker) = channel.recv_waker.take() { waker.wake(); } } } } }

And that's it. We just need a function to construct our channel handles,

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub fn channel<T>() -> (Sender<T>, Receiver<T>) { let channel = Arc::new(Mutex::new(Channel { queue: VecDeque::new(), recv_waker: None, receiver: true, senders: 1, })); let tx = Sender { channel: Arc::clone(&channel), }; let rx = Receiver { channel }; (tx, rx) } }

Chapter 3 - Writing an async mutex

A mutex is a lot like the mpsc channel we just looked at, except the inverse. Much like a channel, it's another commonly reached tool when it comes to concurrent synchronisation, as you saw we used a mutex in the last project as it makes mutating state between concurrent tasks trivial.

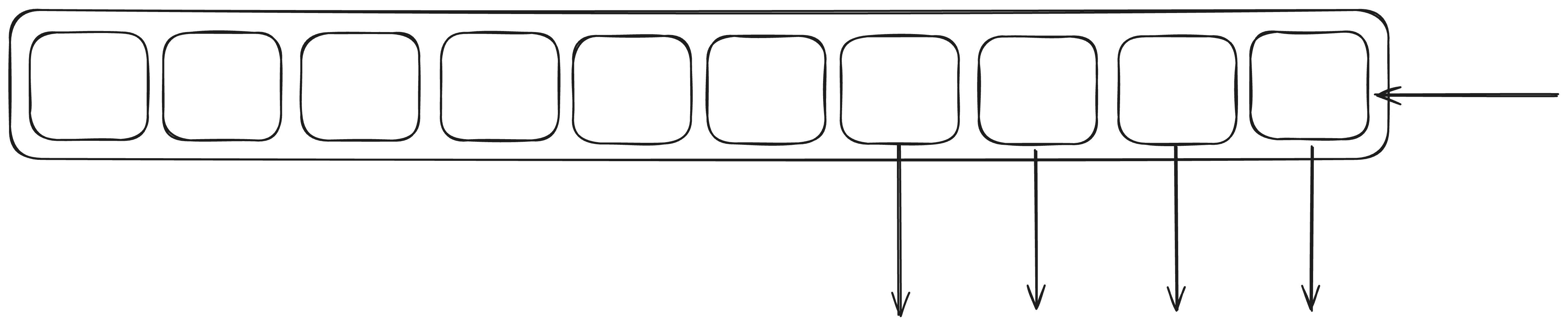

Unlike a channel, which has one waiter, and multiple concurrent writers. A mutex has multiple waiters and one non-concurrent writer. We'll focus on fair mutexes, as that offers some strong latency guarantees, as opposed to faster un-fair mutexes. Because of this fairness requirement, we will need a queue of waiting requests to lock the mutex.

Because of the nature of a mutex, we will need some necessary unsafe in this project. All of the unsafe code you will need is already provided in the project template, and for the sake of the lesson I will not go into the details about why this is necessary.

Much like in the mpsc channel project, we will have some edge cases here too.

Dropping the MutexGuard

If we drop a MutexGuard, we will want to notify the next task in the queue that the mutex is now available. If there is no task currently waiting, we should leave the mutex in a state that indicates it is immediately available.

Dropping a waiting task

While our task is waiting to acquire access to the lock, we might cancel the task before ever getting access.

I haven't mentioned async cancellation yet today, but to since Future's are just data structs inbetween calls to poll, they can be dropped at any time inbetween.

The issue with dropping the waiting task is that it could cause a deadlock. Let's say we drop the waiting task but leave our slot in the waker queue. When the mutex unlocks and tries to wake up the next task, nothing will happen! There will never be another task that can unlock the mutex. So instead, when the task to acquire the lock is dropped early, we should remove our entry from the queue.

One last edge case occurs here. We might drop the waiting task at the same time as we are notified of our access to complete the acquisition of the lock. If this happens, we will need to forward along the notification to the next in line.

Let's think about how we might implement this.

We obviously need a queue for our wakers to live, however we probably cannot use a VecDeque queue like in our channel example. This is because of our need to remove the entries anywhere in the queue on demand.

Instea, we could use a BTreeMap<u64, T> to implement our queue. If we pair this with a monotonically increasing

counter, we can push to the end easily. Just increment the counter and use that as the key into the map.

Additionally, since the BTreeMap is ordered, we can use the provided pop_first() to take the next

waker in the queue when we want to wake one up.

Something like

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct AsyncMutex<T> { queue: Mutex<Queue>, data: UnsafeCell<T>, } struct Queue { /// none if we are just registering our position in the queue. /// some if we have registered the waker /// removed if we have access to acquire the lock wakers: BTreeMap<u64, Option<Waker>>, index: u64, } }

The rest just falls into place after this.

We need to notify a task when dropping out mutex guard

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { impl<'a, T> Drop for AsyncMutexGuard<'a, T> { fn drop(&mut self) { let mut queue = self.mutex.queue.lock().unwrap(); // remove the next entry, signifying it's free to unlock the mutex if let Some(entry) = queue.wakers.pop_first() { // wake up the task if any if let Some(waker) = entry { waker.wake() } } } } }

Now we need to implement the acquire future

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { impl<T> AsyncMutex<T> { async fn lock(&self) -> AsyncMutexGuard<'_, T> { let mut queue = self.queue.lock().unwrap(); // claim a key let key = queue.index; queue.index += 1; // register our interest with no waker queue.wakers.insert(key, None); drop(queue); Acquire { mutex: self, key }.await } } pub struct Acquire<'a, T> { mutex: &'a AsyncMutex<T>, key: u64, } impl<'a, T> Future for Acquire<'a, T> { type Output = AsyncMutexGuard<'a, T>; fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<Self::Output> { let this: &mut Self = &mut *self; let mut queue = self.mutex.queue.lock().unwrap(); // check if we are still in the queue let Some(entry) = queue.wakers.get_mut(self.index) else { // if we are not in the queue, we can acquire the lock! return Poll::Ready(AsyncMutexGuard { mutex: self.mutex }); } // register our waker *entry = Some(cx.waker().clone()); // return pending and wait for another notification Poll::Pending } } }

We also need to handle the acquire drop edge case

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { impl<'a, T> Drop for Acquire<'a, T> { fn drop(&mut self) { let mut queue = self.mutex.queue.lock().unwrap(); // remove our registration if let Some(_entry) = queue.wakers.remove(self.index) { // nothing more to do return; } drop(queue); // since we weren't in the queue, we could have acquired the lock, // so we need to notify the next task. // let's do it simply by dropping the guard we would have acquired. let _ = AsyncMutexGuard { mutex: self.mutex }; } } }

There's one more edge case to handle. The case where there are no more tasks waiting for the lock. We can resolve this by adding an 'unlocked' boolean. If 'unlocked' is set, we skip the queue and resolve the acquired mutex guard immediately, unsetting unlocked at the same time.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Queue { /// none if we are just registering our position in the queue. /// some if we have registered the waker /// removed if we have access to acquire the lock wakers: BTreeMap<u64, Option<Waker>>, index: u64, /// true if the mutex is currently unlocked /// false means you must go to the waker queue unlocked: bool, } impl<'a, T> Drop for AsyncMutexGuard<'a, T> { fn drop(&mut self) { let mut queue = self.mutex.queue.lock().unwrap(); // remove the next entry, signifying it's free to unlock the mutex if let Some(entry) = queue.wakers.pop_first() { // wake up the task if any if let Some(waker) = entry { waker.wake() } } else { // mark the mutex as unlocked queue.unlocked = true; } } } impl<T> AsyncMutex<T> { async fn lock(&self) -> AsyncMutexGuard<'_, T> { let mut queue = self.queue.lock().unwrap(); // claim a key let key = queue.index; queue.index += 1; if queue.unlocked { // skip registering our interest, we can acquire the lock // but lets mark the mutex as locked again queue.unlocked = false; } else { // register our interest with no waker queue.wakers.insert(key, None); } drop(queue); Acquire { mutex: self, key }.await } } }

And that's it! A working asynchronous mutex. Rather than Mutex::lock blocking the thread,

it is able to cooperatively yield until it's actually ready to acquire.

Homework for the reader is to turn it into a more generalised semaphore. Semaphores allow more than 1 task to acquire a work permit, but with a limit. In our case, we have implemented a semaphore with a fixed limit of 1, but we could support more than 1.

Homework++, once you have turned this mutex into a semaphore, could we use this to implement backpressure into our mpsc channel from before.

Chapter 4 - Our first async runtime

As we saw in previous sections, our cooperative tasks boil down to a type that implements Future and

must be repeatedly polled in order to finish. We also have the Context and Waker system

that allows the runtime to sleep if there's currently nothing to do.

If we want our async program to run, then it needs to bridge between async poll-based functions, and non-async blocking functions. Let's look at tokio for example:

#[tokio::main] async fn main() { foo().await; }

If you expand the tokio::main, macro, you will see:

fn main() { let body = async { foo().await; }; #[allow(clippy::expect_used, clippy::diverging_sub_expression)] { return tokio::runtime::Builder::new_current_thread() .enable_all() .build() .expect("Failed building the Runtime") .block_on(body); } }

The key thing to look out for here is this block_on function. It takes the form of

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { /// Turns an async function into a blocking function fn block_on<F: Future>(f: F) -> F::Output { todo!() } }

But how would we write this?

Defining the bare-minimum, we need to build something representing

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { /// Turns an async function into a blocking function fn block_on<F: Future>(f: F) -> F::Output { // futures must be pinned to be polled! let mut f = std::pin::pin!(f); loop { let mut cx: Context = todo!(); match f.as_mut().poll(&mut cx) { Poll::Ready(r) => break r, Poll::Pending => continue, } } } }

But there's two outstanding problems here.

- How do we build our

Context? - How do we allow the thread to sleep while idle

Let's tackle the first problem. There's a bit of a chain we will need to take.

To construct a Context, we can provider a &Waker to the Context::from_waker() function.

So, how do we construct a Waker? Conveniently, there's a impl<W: Wake> From<Arc<W>> for Waker,

so assuming we have some Arc<impl Wake>, we can construct a Waker and thus a Context.

Let's see the Wake trait:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub trait Wake { // Required method fn wake(self: Arc<Self>); } }

All we need to provide is a wake function. Convenient!

For now, let's define it as a no-op. We will take it in the next step.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct SimpleWaker {} impl Wake for SimpleWaker { fn wake(self: Arc<Self>) {} } }

Now, we need to construct the waker and context in our block_on function.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { /// Turns an async function into a blocking function fn block_on<F: Future>(f: F) -> F::Output { // futures must be pinned to be polled! let mut f = std::pin::pin!(f); let root_waker_state = Arc::new(SimpleWaker {}); let root_waker = Waker::from(root_waker_state); loop { let mut cx = Context::from_waker(&root_waker); match f.as_mut().poll(&mut cx) { Poll::Ready(r) => break r, Poll::Pending => continue, } } } }

And now our code should run. Try it!

The only problem is that it uses 100% CPU while it's running. Not great!

Now, how do we tackle the issue of allowing our mini-runtime to sleep.

The Condvar type in the standard library offers a powerful primitive to

allow one thread to Condvar::wait, and then wake up when another thread runs Condvar::notify_one.

Let's introduce a new Runtime struct to contain some useful state.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Runtime { park: Condvar, worker: Mutex<Worker>, } /// Tracks a single runtime worker state. /// Currently we only have 1 worker in our runtime. struct Worker {} }

Then we should update our waker accordingly

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct SimpleWaker { runtime: Arc<Runtime>, } impl Wake for SimpleWaker { fn wake(self: Arc<Self>) { // notify the main thread self.park.notify_one(); } } }

Finally, we need to update our poll-loop to wait on the condvar:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { /// Turns an async function into a blocking function fn block_on<F: Future>(f: F) -> F::Output { // futures must be pinned to be polled! let mut f = std::pin::pin!(f); // create our runtime state let runtime = Arc::new(Runtime { park: Condvar::new(), worker: Mutex::new(Worker {}), }); let root_waker_state = Arc::new(SimpleWaker { runtime: Arc::clone(&runtime), }); let root_waker = Waker::from(root_waker_state); loop { let mut cx = Context::from_waker(&root_waker); match f.as_mut().poll(&mut cx) { Poll::Ready(r) => break r, Poll::Pending => { // park until later let mut worker = runtime.worker.lock().unwrap(); worker = runtime.park.wait(worker); continue; }, } } } }

Theoretically this should all work fine. However, there's a few low-hanging fruits for efficiency.

Should we get a lot of wake() calls, they will all be hitting the Condvar::notify_one even if the worker thread is active.

This is not ideal. Additionally, Condvar::wait is susceptible to 'spurious' wake ups, meaning it can wake up even

if not explicitly notified.

There is also an unfortunate race condition we need to handle where if the task wakes itself up, we don't want to park at all!

Let's update the code one more time to introduce a WorkerState.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Worker { state: WorkerState, } #[derive(PartialEq)] enum WorkerState { /// Is the worker thread currently running a task Running, /// Is the worker thread ready to continue Ready, /// Is the worker thread parked Parked, } }

Next, let's update the waker to action on these states:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { impl Wake for SimpleWaker { fn wake(self: Arc<Self>) { let mut worker = self.worker.lock().unwrap(); if worker.state == WorkerState::Parked { // notify the main parked thread self.park.notify_one(); } // announce there is a task ready. worker.state = WorkerState::Ready; } } }

And finally, let's make sure we keep track of the state while in our loop.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { /// Turns an async function into a blocking function fn block_on<F: Future>(f: F) -> F::Output { // futures must be pinned to be polled! let mut f = std::pin::pin!(f); // create our runtime state let runtime = Arc::new(Runtime { park: Condvar::new(), worker: Mutex::new(Worker { // we start in the running state. state: WorkerState::Running, }), }); let root_waker_state = Arc::new(SimpleWaker { runtime: Arc::clone(&runtime), }); let root_waker = Waker::from(root_waker_state); loop { let mut cx = Context::from_waker(&root_waker); match f.as_mut().poll(&mut cx) { Poll::Ready(r) => break r, Poll::Pending => { let mut worker = runtime.worker.lock().unwrap(); while worker.state != WorkerState::Ready { // park until we are ready later worker.state = WorkerState::Parked; worker = runtime.park.wait(worker); } // resume the loop and mark as running again worker.state = WorkerState::Running; continue; }, } } } }

And just like that, a fully functional single-task runtime that correctly sleeps when not active.

Chapter 5 - Dynamic task allocation

Now that we can run one task in our little runtime. Now is the time to run multiple tasks. I suggest copy-pasting what we already have into the next project file

Again taking inspiration from tokio, we might want to utilise a spawn function that accepts a future and then lazily schedules the task into the runtime.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub fn spawn<F>(f: F) where F: Future<Output = ()> + Send + 'static { todo!() } }

For simplicity, we will pretend that all futures return no values, This might seem like an annoying restriction, but it's not too difficult to work around by inserting your own channel into the task, and it makes the following code quite a bit simpler.

Since we will support any future, we need to store a dynamic collection of futures, Let's start off by defining a helper type-alias

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { type BoxFut = Pin<Box<dyn Future<Output = ()> + Send + 'static>>; }

You'll see we're going to be utilising box-pinning here. Since we want dynamic futures, we need to use dynamic dispatch. Dynamic dispatch is easiest when you use boxed objects, so it just makes sense to use box pinning too.

While we're at it, we know we will likely need a queue of ready tasks - when tasks wake up they need to be scheduled - so let's add a queue to the worker with a stubbed task type. We don't yet know what the task might look like.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct Task {} struct Worker { /// all the spawned tasks that are ready tasks: VecDeque<Task>, state: WorkerState, } }

Next, let's think about our Waker. Ideally, the waker will be able to identify the task directly.

If our runtime had thousands of tasks, we don't want to wake all of them.

A solution we could use is to store the task in the waker so it can be placed into the queue on wake.

Let's adapt our SimpleWaker from before:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct TaskWaker { // we now store a task to push into the runtime worker queue task: Task, runtime: Arc<Runtime>, } impl Wake for TaskWaker { fn wake(self: Arc<Self>) { let mut worker = self.worker.lock().unwrap(); if worker.state == WorkerState::Parked { // notify the main parked thread self.park.notify_one(); } worker.tasks.push_back(self.task.clone()); // announce there is a task ready. worker.state = WorkerState::Ready; } } }

Finally, our worker will need to process the queue of tasks. The task must store a BoxFut type.

And since we need to share the task between the wakers and the runtime, we know the task must store this

behind an Arc. And since polling the future requires mut access, it must therefore also be behind a mutex.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[derive(Clone)] struct Task { fut: Arc<Mutex<BoxFut>>, } }

Now it's your turn to piece this all together

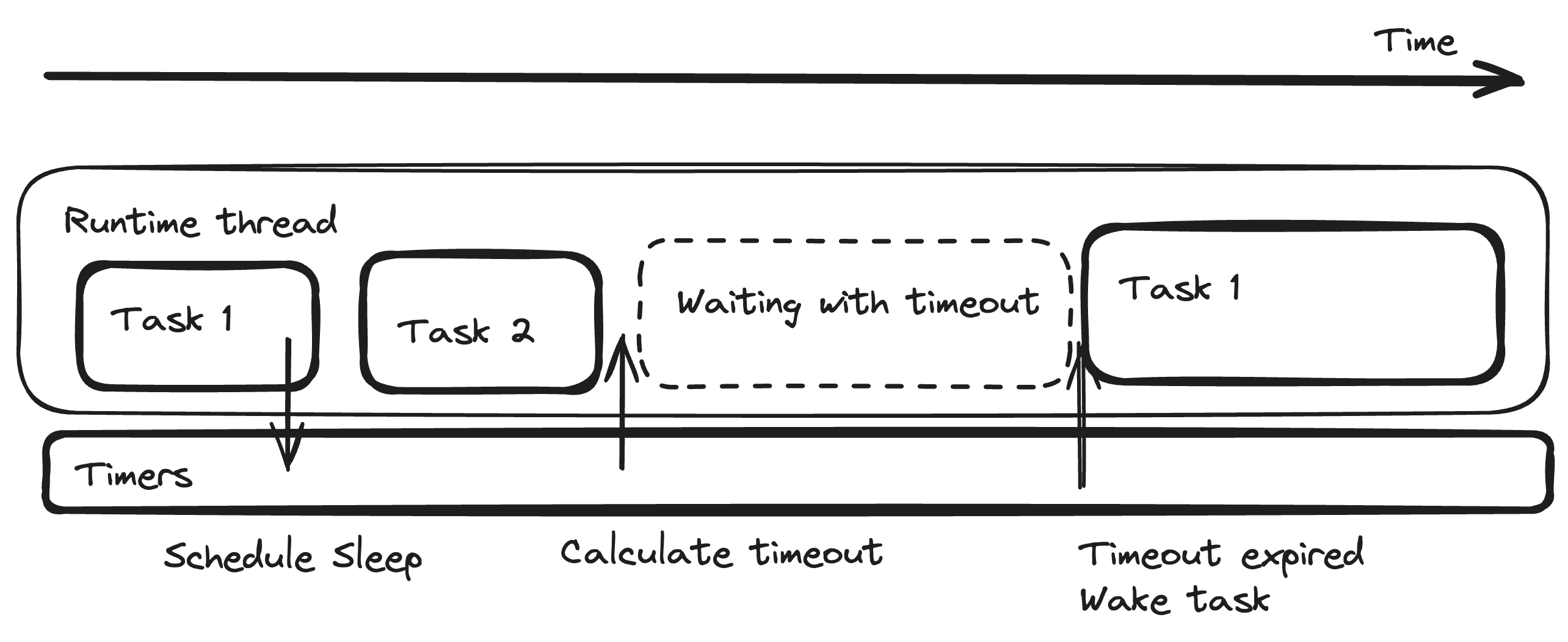

Chapter 6 - Non-blocking timer runtime

Final task - let's add an asynchronous sleep function that makes efficient use of the runtime.

A (not so) trivial async sleep function could work like so:

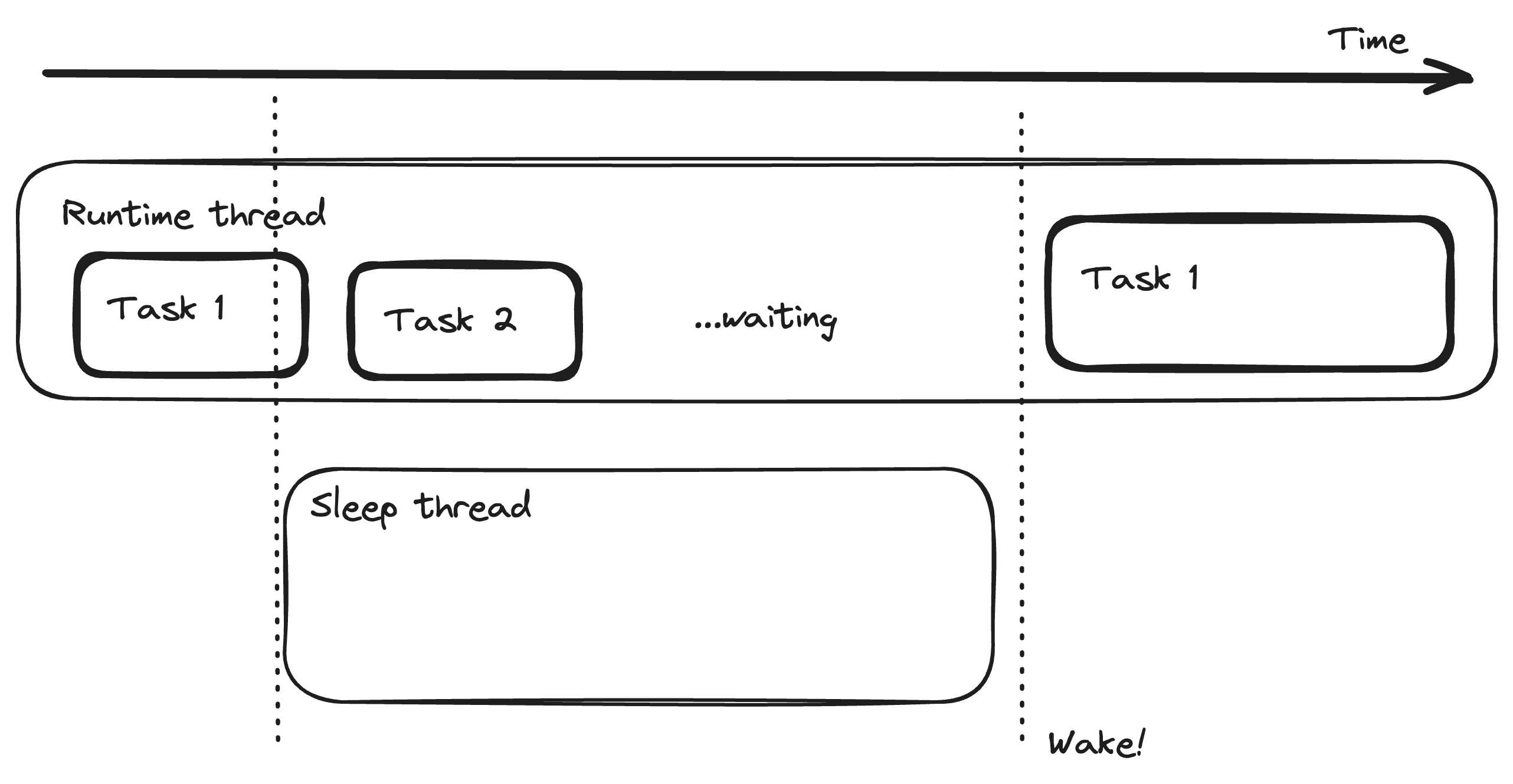

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { async fn sleep(dur: Duration) { let deadline = Instant::now() + dur; std::future::poll_fn(|cx| { let now = Instant::now(); // check if our deadline has expired if deadline <= now { return Poll::Ready(()); } // spawn a thread to sleep // then to wake up the task later let waker = cx.waker().clone(); std::thread::spawn(move || { std::thread::sleep(deadline - now) waker.wake() }); // we are waiting Poll::Pending }).await } }

However, can we avoid spawning a thread per sleeping task? Maybe we could fold it into thread parking functionality as well.

In the previous tasks, we used Condvar::wait to park the thread while idle. Conveniently, there's also

Condvar::wait_timeout which allows us to specify a timeout to immediatly exit on. If we know how long until the next task

might wake up, we can calculate such a timeout and pass it to the condvar.

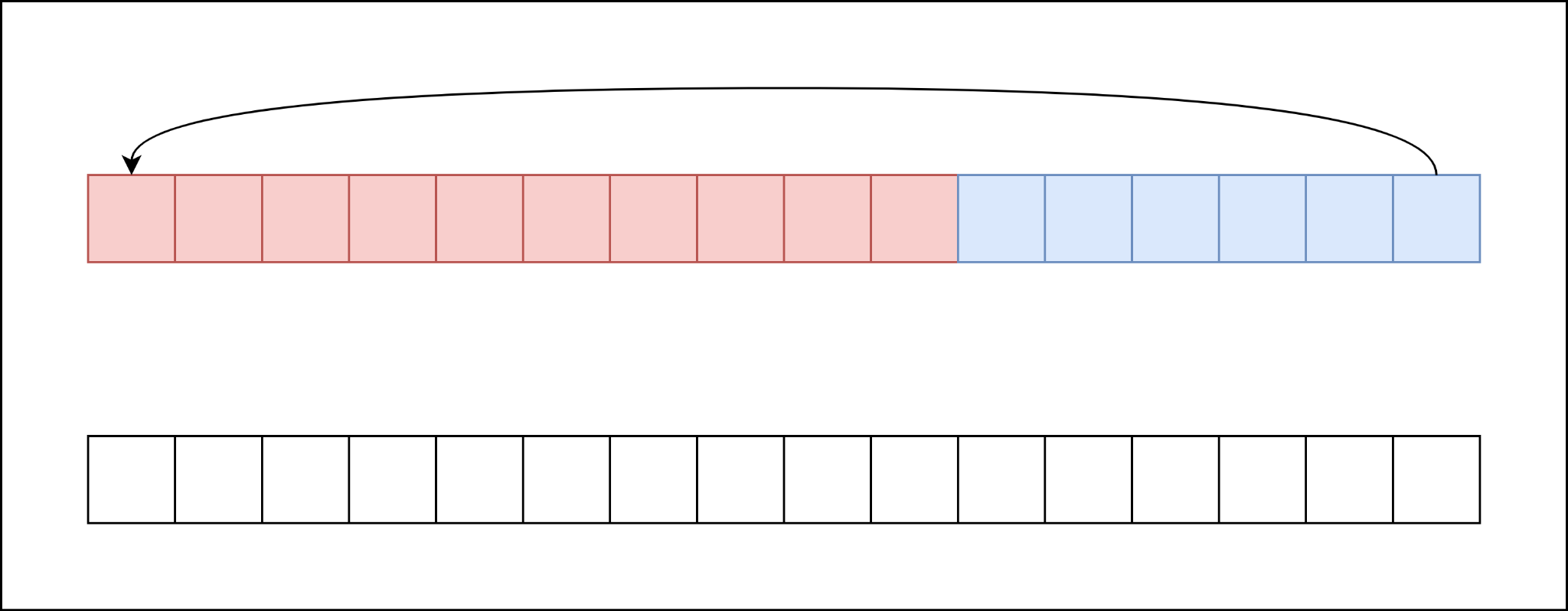

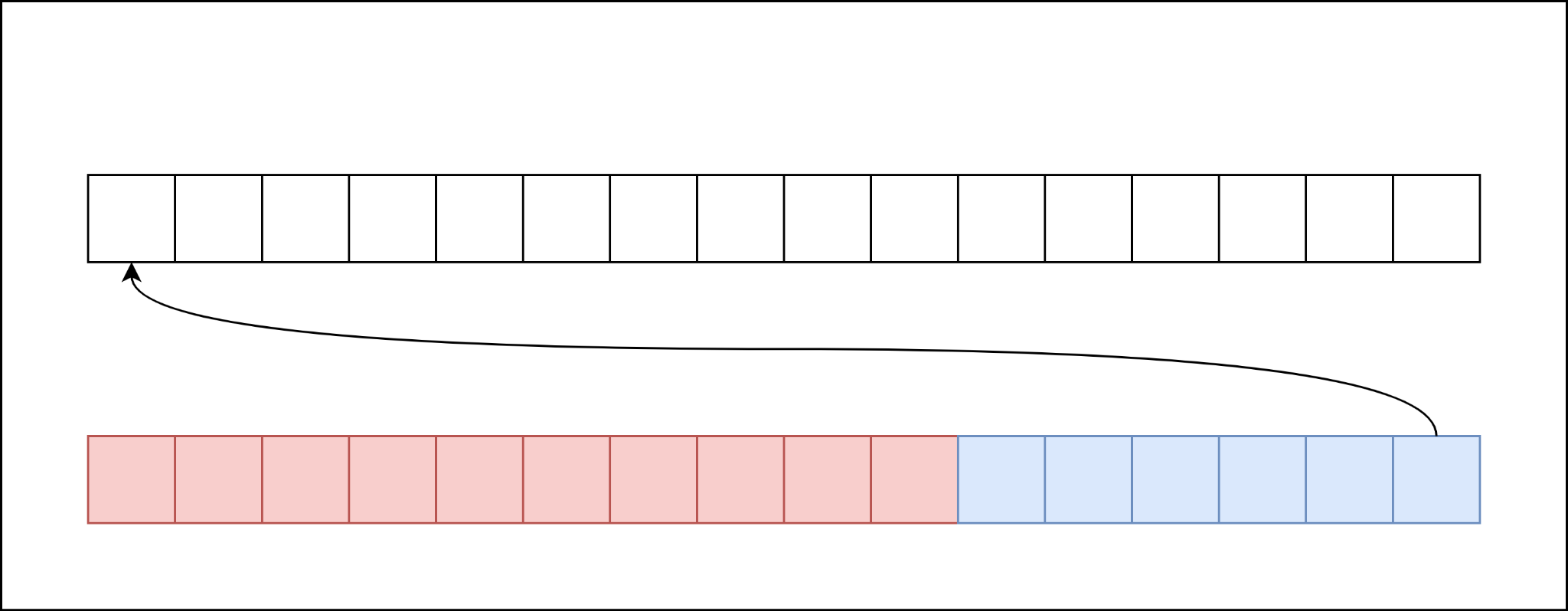

We just need a way to efficiently keep track of all the tasks that might need to wake up. For that, we could

use a min-heap. Rust's standard library offers a max-heap in the form of the BinaryHeap struct. It has efficient

random insert, and efficient pop which takes only the maximum value from the heap. With some Ord boilerplate, we can

smuggle a task waker and turn our max-heap into a min-heap over the deadline Instant.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // timers: BinaryHeap<TimerEntry> struct TimerEntry { deadline: Instant, waker: Waker, } impl PartialEq for TimerEntry { fn eq(&self, other: &Self) -> bool { self.deadline == other.deadline } } impl Eq for TimerEntry {} impl PartialOrd for TimerEntry { fn partial_cmp(&self, other: &Self) -> Option<std::cmp::Ordering> { Some(self.cmp(other)) } } impl Ord for TimerEntry { fn cmp(&self, other: &Self) -> std::cmp::Ordering { // BinaryHeap works as a max-heap. // We want a min-heap based on deadline, so we should reverse the order. self.deadline.cmp(&other.deadline).reverse() } } }

Now it's your turn to piece this all together